The Ongoing Chip Wars

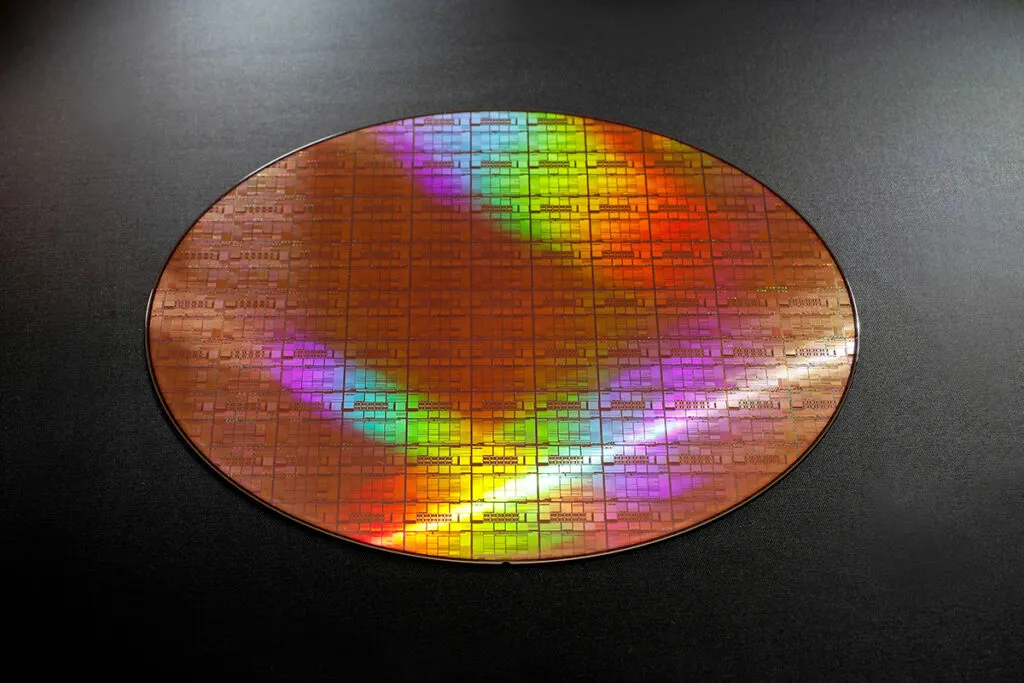

It feels like yesterday that the industry was celebrating 14nm technology, but in reality, that milestone is now a distant memory. It’s now 2025, and companies are pushing the limits of silicon to 2nm, with Intel actively targeting the 18-angstrom barrier. The pace of miniaturization is both impressive and absurd, but when scaling transistors down to such atomic dimensions, engineers are faced with all kinds of complications that go far beyond standard material science challenges.

At the atomic scale, quantum effects stop being a minor nuisance and dominate transistor behavior. Electrons no longer follow predictable path, where tunneling and leakage currents become central concerns, and the placement of individual atoms can dictate performance.

Designing transistors at these scales requires precise manipulation of matter where a single misplaced atom can compromise functionality. Furthermore, high transistor densities only exacerbate the problem, with thermal management becoming critical as densely packed devices struggle to dissipate heat efficiently. At such small sizes, even brief voltage spikes can irreversibly damage components that have no tolerance for error. Traditional lithography has also reached its practical limits. Standard optical techniques, which have powered the semiconductor industry for decades, cannot reliably image features measured in atoms, forcing manufacturers to adopt exotic imaging and patterning methods.

Extreme ultraviolet lithography, the current method for atomic lithography, is state of the art, but all equipment used in this process is produced by a single company (ASML), creating a serious bottleneck. This monopoly constrains experimentation and slows progress for companies attempting to explore atomic-level transistor architectures.

When all of these concerns are brought together, it becomes clear that the pursuit of smaller, faster chips is no longer a simple exercise in shrinking dimensions, but a careful balancing act between physics, materials science, and industrial logistics.

Rapidus 2HP Reportedly Surpasses Intel 18A in Logic Density, Rivals TSMC

Rapidus is preparing its 2nm node, “2HP,” which sources indicate will achieve logic density on par with TSMC’s N2 and notably ahead of Intel’s 18A. According to reports cited by Wccftech, Rapidus 2HP is expected to reach 237.31 MTr/mm², slightly above TSMC’s 236.17 MTr/mm². Both nodes rely on High Density (HD) cell libraries, 138-unit cell height on a G45 pitch, indicating comparable transistor counts.

Intel’s 18A node, by contrast, is reported at 184.21 MTr/mm². The lower density is attributed to BSPDN, which occupies part of the front-side metal layers and reduces effective HD library packing. Intel prioritizes performance-per-watt over raw density, and 18A is largely intended for internal deployments rather than pushing transistor counts.

Rapidus plans to release its 2nm PDK in Q1 2026, with mass production targeted for 2027. Sources indicate the company has already taped out a 2nm GAA test chip using ASML EUV tools, meeting its initial electrical specifications. The IIM-1 fab is projected to produce roughly 25,000 wafers per month once full production begins.

Even by 2027, Rapidus may still trail TSMC by one or two nodes and could lag Intel in certain performance metrics. The company’s differentiation lies in its manufacturing agility: a proprietary all-single-wafer process with a 50-day turnaround, compared with approximately 120 days for standard batch–single-wafer operations. Rapidus’ approach prioritizes speed and flexibility over absolute node leadership, a strategy that could pay off in niche high-performance markets.

Are Process Nodes Still Relevant?

For decades, node size was the shorthand for semiconductor performance. Smaller nodes meant higher logic density, lower power consumption, and, implicitly, superior chips. The industry equated shrinking transistors with progress being simple, linear, and measurable.

That model, as shown with Rapidus, is breaking down. With nodes approaching the angstrom scale, raw transistor size no longer guarantees meaningful gains. A smaller transistor does not automatically translate into smaller logic units or higher-performing devices. What matters now is who can deliver the most cost-effective, reliable, high-density designs that actually support modern workloads. Intel’s own devices over the past few years illustrate this shift: older nodes have occasionally outperformed newer, smaller ones in real-world metrics.

So what we see now is that shrinking alone is not the answer. For many applications, stacking, 3D integration, and other architectural innovations may offer more tangible benefits than chasing the next node. The race is no longer just about who can etch the smallest transistor, it’s about who can turn extreme miniaturization into usable, efficient hardware.