The Rising Chip Shortage

It feels uncomfortably recent, but the COVID pandemic of 2020 fundamentally reshaped the electronics industry. What began as a public health crisis quickly cascaded into financial instability, fractured logistics, and a supply chain failure that exposed just how brittle global semiconductor manufacturing really was. Markets crashed, factories shut down, shipping stalled, and the carefully optimized just-in-time model collapsed almost overnight.

For engineers, the effects were immediate and extremely painful, with component shortages becoming severe enough to cause extreme desperation. In some cases, manufacturers were buying finished consumer products, tearing them down, and harvesting the integrated circuits inside simply because sourcing the bare components through normal channels was impossible. Lead times stretched from weeks into years, prices became meaningless, and designs that had been stable for a decade could suddenly not be built.

Five years on, the situation has improved, but it has still not fully recovered. Shortages continue to exist in key areas, particularly around power management, analog ICs, and certain classes of memory. The difference now, however, is that engineers have adapted to sudden supply chain disruptions. Supply chain risk is actively designed for rather than treated as an afterthought., and second sources are now a mandatory requirement. Furthermore, firmware abstraction layers are being introduced to specifically to allow part substitutions, and inventory strategies are far more conservative. The industry learned, painfully, how to cope.

Unfortunately, just as that hard-earned stability began to return, a new pressure entered the system. The explosion of AI investment over the past few years has created a fresh and highly asymmetric demand shock. Data centers consume enormous quantities of silicon, and not just exotic accelerators; RAM has been hit particularly hard with DDR4 and DDR5 prices having surged, in some cases nearly tripling, driven largely by hyperscale demand rather than consumer electronics.

The knock-on effects of this demand extend well beyond memory pricing. AI infrastructure consumes vast amounts of energy and water, stressing utilities and regional resources alongside fabs themselves. Semiconductor suppliers, responding rationally to where the money is, are increasingly prioritizing AI-focused products. Capital, engineering talent, and wafer capacity are also being redirected toward accelerators, high-bandwidth memory, and advanced packaging, which further compounds issues in the industry. From a business perspective, this makes sense, but from a broader industry perspective, it leaves everyone else competing for what is left.

TSMC Warns Major Chip Companies of Supply Constraints

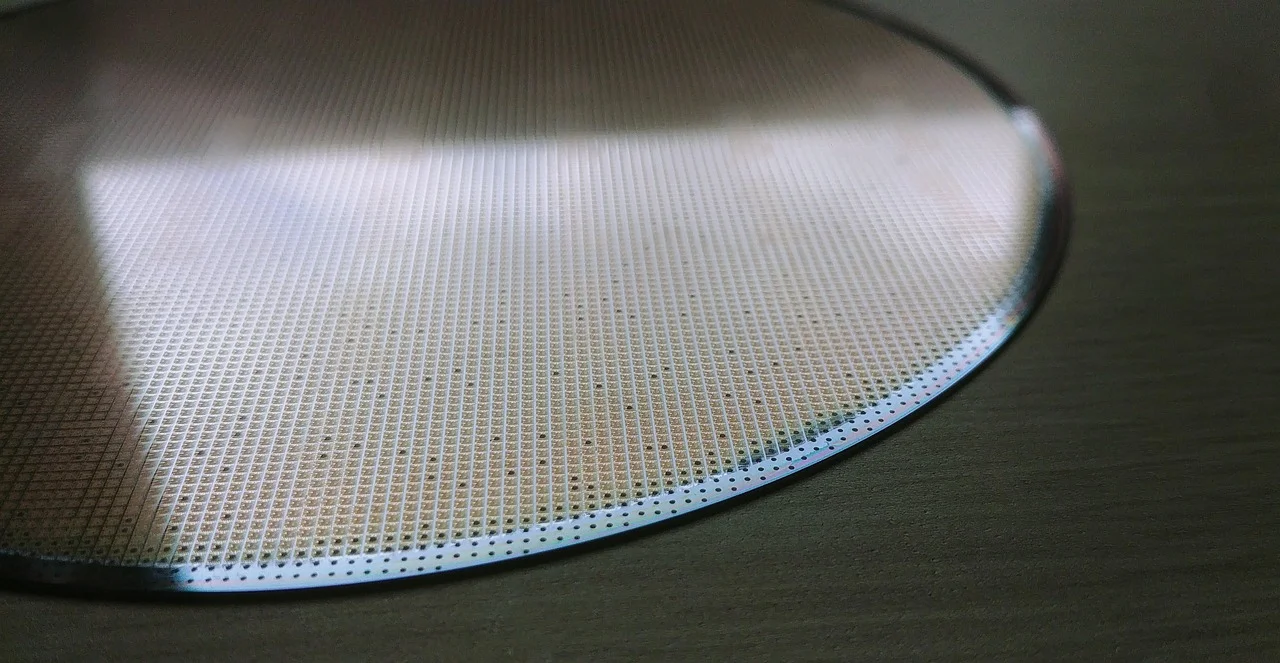

These semiconductor pressures are now becoming increasingly more visible at the highest levels of industry. TSMC, one of the most important manufacturer of semiconductor devices, has reportedly warned major customers including Nvidia and Broadcom that capacity for advanced AI chips is constrained. Lead times for cutting-edge process nodes now extend across multiple quarters, even for companies accustomed to preferential access. Demand for AI accelerators and supporting infrastructure silicon is surging globally, and there is simply not enough advanced capacity to satisfy everyone at once.

Hyperscale cloud providers and chip designers are now effectively competing for allocation slots at foundries, and this is by no means a normal market dynamic. Access to manufacturing has become a strategic advantage, and in some cases, a limiting factor on growth. Even well-funded companies with proven designs are finding that money alone does not buy immediate capacity when the fabs are already full.

This environment has created an unexpected opportunity for business like Intel. Long criticized for manufacturing delays, Intel’s foundry ambitions are suddenly more credible simply because alternatives are constrained. For customers unable to secure sufficient TSMC capacity, Intel represents an option that did not exist a few years ago, and investor confidence in Intel has now responded accordingly, buoyed by the possibility of significant foundry orders from companies desperate to diversify risk.

Meanwhile, TSMC itself continues to post strong earnings, exceeding expectations despite these capacity limits. Of course, demand is not the problem, but the supply is. The company has signaled increased capital spending into 2026 to expand production, but semiconductor fabs are not built quickly. Even aggressive investment takes years to translate into usable wafer output. Until then, constraints remain baked into the system.

Are We Ever Going to See Supplies Normalise?

There is an uncomfortable pattern emerging in the semiconductor space (and electronics space in general). As technology advances, our ability to meet demand seems to get worse rather than better. New technologies no longer arrive gradually, but instead arrive explosively, reshape markets in months, and create demand curves that suppliers cannot realistically anticipate or absorb. Worse, this cycle appears to be accelerating, with major technological shifts now arriving yearly, not generationally.

AI is a perfect example of this shift. The hardware requirements of early models look nothing like those of today’s systems, with each iteration demanding different accelerators, different memory configurations, and different interconnect strategies. That constant churn makes long-term capacity planning almost impossible. By the time manufacturing catches up to one wave, the next has already arrived.

In theory, there must be a future point where things stabilize in these technology spaces. But in practice, no one knows where that point is, or whether it exists at all (if anyone could determine this, they would undoubtedly make untold profits from stock markets). One possible response is not to chase the latest nodes endlessly, but to rebalance manufacturing toward older, well-understood technologies. Not every electronic product needs five-nanometer silicon, and many systems would benefit more from stable supply, predictable pricing, and long-term availability than from marginal performance gains.

This concept also raises the possibility of a more decentralized manufacturing model. Passive components, discrete transistors, and basic logic elements could be produced in smaller, localized facilities serving fewer customers, with some component manufacturing possibly moving closer to in-house production. Printed electronics already allow resistors and capacitors to be fabricated directly at the PCB level in certain applications.

For now, however, the industry remains heavily dependent on a small number of massive manufacturers. That concentration made sense when demand was predictable and growth was incremental. In a world driven by rapid, AI-fueled demand spikes, it looks increasingly fragile. Until manufacturing capacity, technology cadence, and demand patterns realign, engineers and manufacturers alike will continue to operate in a state of managed scarcity. And the next big technology wave will almost certainly make it worse before it gets better.