Japanese Enthusiast Builds a 128-Byte USB Core Memory

Magnetic core memory first appeared in real, working computers in 1953 with MIT’s Whirlwind project, and, for roughly two decades after that, it was the dominant form of random-access memory in everything from room-sized mainframes to early minicomputers. This was not because it was elegant or efficient, but because nothing better existed at the time. Core memory solved a critical problem that earlier approaches could not; it was reasonably fast, randomly addressable, and crucially, it retained data when power was removed.

At a physical level, core memory is incredibly simple. Each bit is stored in a tiny ferrite ring, or core, threaded by multiple wires. One set of wires selects a row, another selects a column, and a third senses the result, while the direction of magnetization in the ring represents the binary state (1 or 0). However, in order to read a bit, the core bit needs to be forced into a known state, making it a destructive read process. Thus, once read, the original state needs to be re-written into that bit.

The drawbacks to magnetic core memory are obvious to anyone used to modern memory. The density is abysmal, cost scales directly with manual labor, since each core plane must be woven by hand or by specialized machinery that never scaled well, power consumption is high, switching speed is limited, and expanding capacity rapidly becomes impractical. Once Intel introduced the 1103 DRAM in 1970, core memory faded into memory (pardon the pun). Unlike core memory, semiconductor based technologies were cheaper, denser, faster, and far easier to integrate.

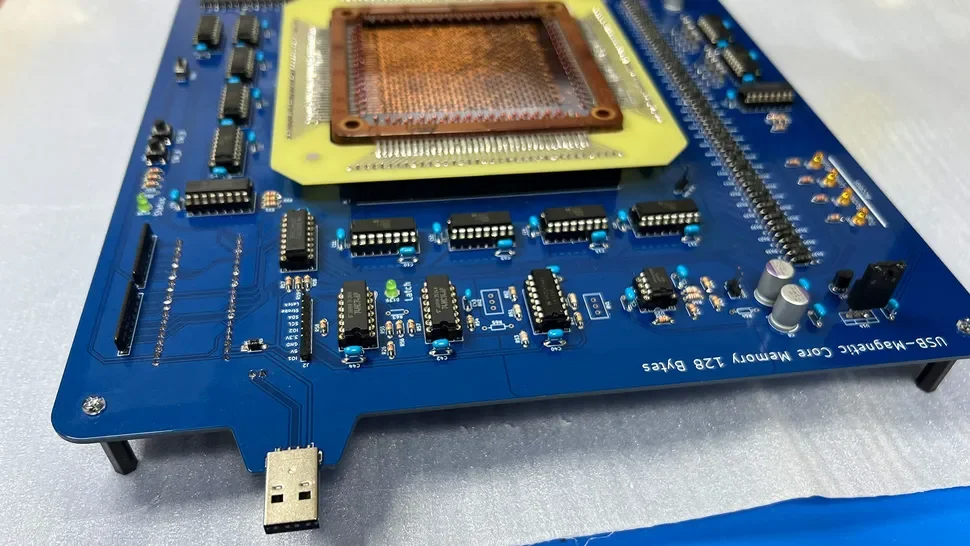

But not all want to see such technologies disappear. One Japanese electronics enthusiast recently built a modern magnetic core memory device as a personal experiment, with the result being a dinner-plate-sized USB storage device with a total capacity of 128 bytes. Now, that number is not missing any zeros, it only contains 128 bytes total. The device combines a hand-built core plane with modern support electronics, including driver circuitry, sense amplifiers, indicator LEDs, and a Raspberry Pi Pico that handles USB communication and rewrite control.

From a practical point, this device is useless as storage; even a single JPEG thumbnail would overwhelm it. But for this project, that is far from the point. The project exists as a proof of concept and a physical demonstration of why core memory vanished. By interfacing a 1950s memory technology with a modern USB stack, the builder exposes the full absurdity of the mismatch. Despite all of that, this project is hands down one of the most intriguing ones I have ever seen in the field of retro technologies.

Why Projects Like This Are Worth Exploring

Magnetic core memory has been obsolete for more than half a century, with most practicing engineers never seeing it outside of museum displays. It is slow, difficult to manufacture, nearly impossible to scale, and fundamentally incompatible with modern expectations of density and cost. And yet, this same old antiquated technology that would never work today helped land humans on the Moon.

Recreating obsolete technologies forces engineers to confront the physical realities that modern tech often hide. When you build core memory, you cannot ignore inductance, hysteresis, sense thresholds, or noise margins, and each bit has mass, geometry, and tolerance.

There is also an educational value that goes beyond nostalgia, as understanding how older technologies worked clarifies why modern architectures look the way they do. DRAM refresh cycles make more sense when you have dealt with destructive reads, and error correction stops feeling optional when a slight timing error flips a bit.

But there is also a stranger angle to exploring ancient technologies. While macroscopic rope memory and ferrite cores are clearly dead ends, their underlying principles are not. Magnetic spin-based storage and memory elements, for example, are actively researched at the nanoscale. Likewise, vacuum tubes are obsolete at human scale, but vacuum-channel transistors at nanometer dimensions are being explored as potential successors to silicon. Such devices promise faster switching and improved tolerance to radiation and heat, at least in theory.

Despite their age, old ideas rarely disappear completely. They shrink, mutate, and re-emerge in forms that would have seemed absurd to their original inventors. Playing with obsolete technology is not about pretending the past was better, it’s about understanding the full design space, including the parts we abandoned for good reasons.

What Could Be Next

Magnetic core memory is already a challenging project, both mechanically and electrically. Completing a working system, even one limited to 128 bytes, requires patience, precision, and a solid grasp of analog behavior. But with magnetic core memory accomplished, it begs the question what comes next? What other historical computing technologies could be dragged into the present, kicking and screaming, by determined enthusiasts?

One candidate that comes to mind, albeit somewhat dangerous, is mercury delay lines. These early memory systems stored data as acoustic pulses traveling through liquid mercury. Bits were read sequentially as pressure waves arrived at a transducer, making access times both slow and inflexible. Rebuilding one today with modern sensors and control electronics would be half science experiment, half mad. However, it would also be an excellent demonstration of why random access was such a breakthrough.

Magnetic tape memory is another option, though interestingly, it still exists in modern data centers in a far more refined form. A deliberately crude, early-style tape memory system would highlight just how much complexity is hidden inside modern tape drives. Timing, tension control, error correction, and encoding schemes quickly become the real story.

Paper tape is perhaps the most absurd, and thus, potentially the most tempting technology to try out. Encoding data as physical holes in a strip of paper and interfacing it to a USB host would be a masterclass in inefficiency, but also show how such technologies formed the foundation of modern digital systems.

All of these technologies are obsolete for good reasons, and none of them should be revived for practical use. But as educational tools and engineering challenges, they remain incredibly valuable. They expose assumptions, punish sloppy thinking, and reward careful design. In an industry increasingly abstracted away from physical reality, that kind of grounding is rare.

Rebuilding the past does not move technology forward directly. What it does is sharpen the people who will.